Grand Central Terminal is one of two magnificent train stations that were built in New York in the heyday of railway transportation. The other, Penn Station, was demolished in the 1960s.

The monumental railway station was constructed in 1903-1913 for the New York and Harlem Railroad company. It is a grand Beaux-Arts building which serves as a transportation hub connecting train, metro, car and pedestrian traffic efficiently. It has 67 train tracks on two different levels.

Penn Station

The other, even grander railway station – Penn Station – was built in 1902-1911 after a design by Charles McKim. In an act of vandalism, the monumental landmark – which was modeled on the ancient Baths of Caracalla in Rome – was destroyed in 1963-1966 and replaced by a banal railway station and office tower.

Grand Central Terminal almost suffered a similar fate, but thanks to New York City’s new landmark preservation laws – implemented in part thanks to the outcry over the demolition of Penn Station, the building was able to escape the wrecking ball.

The First Grand Central Station

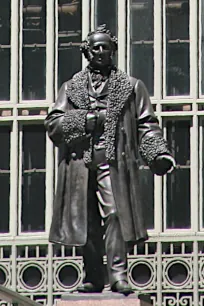

The current Grand Central Terminal was not the first railway station at 42nd Street and Park Avenue. As early as in 1863 Cornelius Vanderbilt, known as ‘the Commodore’ consolidated railroad lines including the Harlem Railroad and New York Central Railroad. As a result of the consolidation, the need for a large railway station soon became apparent.

In 1869, Vanderbilt commissioned architect John B. Snook to build the largest railway station in the world on a large property at 42nd Street. The resulting station, named Grand Central Station, featured a large glass and steel train shed, 650ft long, 200ft wide and 100ft high (198 x 60 x 30 meters). But increasing traffic and the smoke from the steam engines obscured vision in the Park Avenue tunnel, causing an accident in 1902. Seventeen people were killed, and a public outcry called for electrification of the railway system. This resulted in a new state law requiring that steam engines would not be allowed in Manhattan, starting in 1910.

A New Railway Station

Shortly after the accident, the New York Central Railroad proposed plans for a new, larger Grand Central Station. The costly electrification and construction of the new railway station was compensated by the use of air rights: Electrification made it possible for the tracks to be covered and paved over all the way to 49th Street. Developers were allowed to construct buildings on top of it, but had to pay an extra sum to the railway company, the so-called air rights. Even the air on top of low-level buildings can be sold this way so that taller neighboring buildings are allowed.

In 1903 a competition was held for the design of the new Grand Central. The firm of Reed and Stem was chosen. William K. Vanderbilt II, one of the descendants of the ‘Commodore’ asked Warren and Wetmore to collaborate with Reed and Stem. While the latter were responsible for the overall design and layout, Warren and Wetmore were responsible for the architectural details and Beaux-Arts style.

Terminal City

The project included not just the new railway station, but a whole complex with office buildings and apartments, which became known as ‘Terminal City’. This was a ‘city in the city’ complex, similar to the concept of Rockefeller Center, created several decades later. Special attention was paid to the circulation of traffic. Pedestrians and cars are separated by special elevated ramps – the so-called Park Avenue Viaduct – which lead the cars around the railway station.

Construction of the new station, now known as Grand Central Terminal, lasted ten years and cost eighty million dollars. In the process, 180 buildings between 42nd and 50th Street, including hospitals and churches, were demolished. The railway station officially opened on Sunday, February 2, 1913. But it would last until 1927 before the station was fully operational.

A Grand Design

The building’s facade on 42nd Street has a true Beaux-Arts design. Large arches flanked by Corinthian columns are topped by a large sculpture group designed by Jules-Alexis Coutan. The 50 ft. / 15 m. high artwork depicts Mercury (the god of commerce) supported by Minerva and Hercules (representing mental and moral strength).

Inside, the main concourse is most impressive. It is 470 feet long, 160 feet wide and 150 feet high (143 x 49 x 43 meters). The ceiling was painted by the French artist Paul Helleu. The design with zodiac constellations was taken from a medieval manuscript. It is painted backwards, allegedly so that the stars are shown as they would be seen by god, not by man.

Light enters the main concourse through six 75 ft. / 23 m. high arched windows. The western double staircase in Botticino marble was designed after the large staircase in the Opera Garnier in Paris. It connects the main concourse with the entrance on Vanderbilt Avenue. The floor of the concourse is of Tennessee marble, the walls of Caen stone.

Redevelopment

In 1994, the firms of LaSalle Partners and Williams Jackson Ewing were chosen by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) to redevelop Grand Central Terminal. The firms were chosen for their successful renovation of another Beaux-Arts icon, the Union Station in Washington, DC.

The MTA’s goal was to increase revenue while restoring the building’s former grandeur. This was achieved by renovating the large public areas, removing former alterations (like lowered ceilings), adding a new entrance and creating a retail mall and food court, similar to the renovation project in Washington, DC.

During the 197 million dollar restoration process, a large iron eagle was added on top of the new Lexington Avenue & 43rd Street entrance. This eagle once adorned the first Grand Central Station in 1898.